PID

Our previous attempt at creating a controller that used feedback from the robot could be further improved by considering how the error (difference between feedback value and the goal) changes over time.

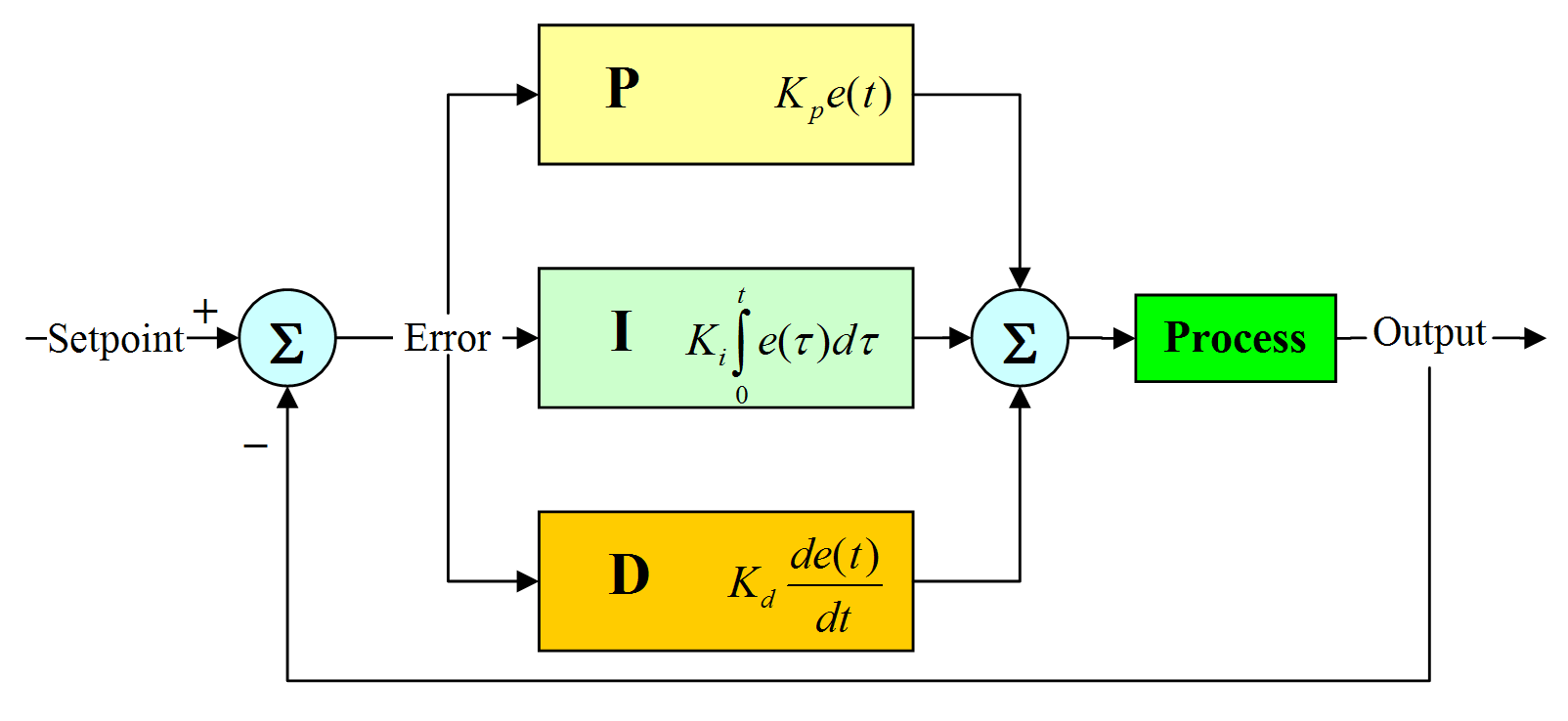

Since PID is an abbreviation, let’s talk about that the terms \(P\), \(I\) and \(D\) mean:

- \(P\) stands for proportional – how large is the error now (in the present).

- \(I\) stands for integral – how large the error was in the past.

- \(D\) stands for derivative – what will the error likely be in the future.

The controller takes into account what happened, what is happening, and what will likely happen, and combine these things to produce the controller value.

Deriving the equations

Before diving into the equations, we need to define a terms to build the equations from:

- \(e\) – the current error (difference between robot position and its goal).

- \(\Delta e\) – difference between the current and the previous error.

- \(\Delta t\) – time elapsed since the last measurement.

- \(p, i, d\) – constants (positive real numbers) to determine, how important each of the terms are. This make it so that we can put more emphasis on some parts of the controller than others (or ignore them entirely).

Proportional

Proportional is quite straight forward – it only takes into account, how big the error is right now.

\[P = e\]The problem with only using only \(P\) is that the closer we get to the goal, the smaller the value of this term is. The robot’s movement would feel stiff and there is a chance that it wouldn’t even reach the goal. That’s why it needs to be complemented by the other parts, for the controller to be effective.

Integral

Integral adds the extra push that the proportional was missing, because it doesn’t react to what is happening right now, but to what was happening in the past, by accumulating the error.

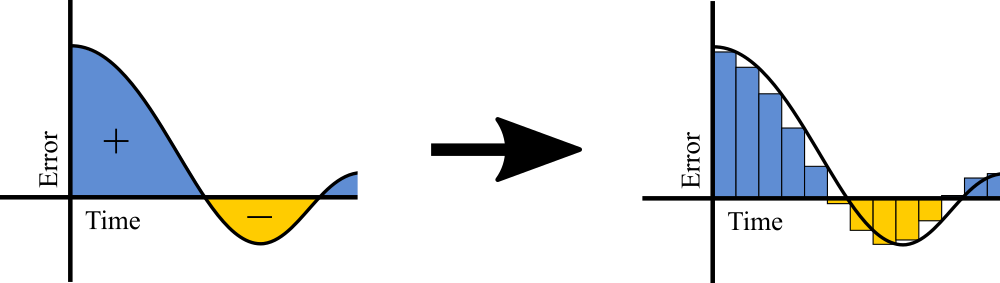

Calculating an integral means calculating area under a curve (in our case, the curve is error over time). With real-world measurements, we can’t calculate the actual area, because we can only call the code so many times a second. That’s why we will approximate the area by calculating rectangles that closely resemble the curve.

For each computation, the height of the rectangle is the error \(e\), and width is the elapsed time \(\Delta t\) since the last measurement. To calculate the rectangular area, we multiply these two numbers together. \(I\) itself is the sum of all of these values.

\[I \mathrel{+}= e \cdot \Delta t\]This can, however, introduce additional instability to the controller, since the values can accumulate and cause overshoot, and the reaction could also potentially be slow, due to windup.

Derivative

Derivative aims to further improve the controller by damping the values. We will calculate the rate of change of the error to predict its future behavior – the faster the robot goes, the bigger \(\Delta e\) is, and the more it will push back against the other terms.

\[D = \frac{\Delta e}{\Delta t}\]A note to be made is that if \(\Delta t = 0\), the derivative can’t be calculated, because we would be dividing by zero – just something to keep in mind for the implementation.

Result

As we have previously said, the result is adding all of those terms, multiplied by their constants (determines the importance of the terms in the result).

\[P \cdot p + I \cdot i + D \cdot d\]The only thing we need to keep in mind is that the values could exceed \(1\) (or \(-1\)). If they do, we will simply return \(1\) (or \(-1\)).

Implementation

The controller will need the \(p\), \(i\) and \(d\) constants. It will also need a feedback function and, to correctly calculate the integral and derivative, a function that returns the current time.

class PID:

"""A class implementing a PID controller."""

def __init__(self, p, i, d, get_current_time, get_feedback_value):

"""Initialises PID controller object from P, I, D constants, a function

that returns current time and the feedback function."""

# p, i, and d constants

self.p, self.i, self.d = p, i, d

# saves the functions that return the time and the feedback

self.get_current_time = get_current_time

self.get_feedback_value = get_feedback_value

def reset(self):

"""Resets/creates variables for calculating the PID values."""

# reset PID values

self.proportional, self.integral, self.derivative = 0, 0, 0

# reset previous time and error variables

self.previous_time, self.previous_error = 0, 0

def get_value(self):

"""Calculates and returns the PID value."""

# calculate the error (how far off the goal are we)

error = self.goal - self.get_feedback_value()

# get current time

time = self.get_current_time()

# time and error differences to the previous get_value call

delta_time = time - self.previous_time

delta_error = error - self.previous_error

# calculate proportional (just error times the p constant)

self.proportional = self.p * error

# calculate integral (error accumulated over time times the constant)

self.integral += error * delta_time * self.i

# calculate derivative (rate of change of the error)

# for the rate of change, delta_time can't be 0 (divison by zero...)

self.derivative = 0

if delta_time > 0:

self.derivative = delta_error / delta_time * self.d

# update previous error and previous time values to the current values

self.previous_time, self.previous_error = time, error

# add P, I and D

pid = self.proportional + self.integral + self.derivative

# return pid adjusted to values from -1 to +1

return 1 if pid > 1 else -1 if pid < -1 else pid

def set_goal(self, goal):

"""Sets the goal and resets the controller variables."""

self.goal = goal

self.reset()

To fully understand how the controller works, I suggest you closely examine the get_value() function – that’s where all the computation happens.

Notice a new function called reset that we haven’t seen in any of the other controllers. It is called every time we set the goal, because the controller accumulates error over time in the integral variable, and it would therefore take longer to adjust to the new goal.

It doesn’t change the versatility of the controller classes, because we don’t need to call it in order for the controller to function properly, it’s just a useful function to have.

Tuning the controller

PID is the first discussed controller that needs to be tuned correctly to perform well (besides dead reckoning, where you have to correctly calculate the average speed). Tuning is done by adjusting the \(p\), \(i\) and \(d\) constants, until the controller is performing the way we want it to.

There is a whole section on Wikipedia about PID tuning. We won’t go into details (read through the Wikipedia article if you’re interested), but it is just something to keep in mind when using PID, because incorrect tuning could have disastrous results.

Examples

Driving a distance

Here is an example that makes the robot drive 10 meters forward. The constants are values that I used on the VEX EDR robot that I built to test the PID code, you will likely have to use different ones.

# initialize objects that control robot components

left_motor = Motor(1)

right_motor = Motor(2)

encoder = Encoder()

# create a controller object and set its goal

controller = PID(0.07, 0.001, 0.002, time, encoder)

controller.set_goal(10)

while True:

# get the controller value

controller_value = controller.get_value()

# drive the robot using tank drive controlled by the controller value

tank_drive(controller_value, controller_value, left_motor, right_motor)

Auto-correct heading

Auto-correcting the heading of a robot is something PID is great at. What we want is to program the robot so that if something (like an evil human) pushes it, the robot adjusts itself to head the way it was heading before the push.

We could either use values from the encoders on the left and the right side to calculate the angle, but a more accurate way is to use a gyroscope. Let’s therefore assume that we have a Gyro class whose objects give us the current heading of the robot.

One thing we have to think about is what to set the motors to when we get the value from the controller, because to turn the robot, both of the motors will be going in opposite directions. Luckily, arcade_drive is our savior – we can plug our PID values directly into the turning part of arcade drive (the x axis) to steer the robot. Refer back to the Arcade Drive article, if you are unsure as to how/why this works.

# initialize objects that control robot components

left_motor = Motor(1)

right_motor = Motor(2)

gyro = Gyro()

# create a controller object and set its goal

controller = PID(0.2, 0.002, 0.015, time, gyro)

controller.set_goal(0) # the goal is 0 because we want to head straight

while True:

# get the controller value

controller_value = controller.get_value()

# drive the robot using arcade drive controlled by the controller value

arcade_drive(controller_value, 0, left_motor, right_motor)

Closing remarks

PID is one of the most widely used controllers not just in robotics, but in many other industries, because it is reliable, relatively easy to implement and quite precise for most use cases.

For motivation, here is a video demonstrating the power of a correctly configured PID controller.